Estimated reading time 11 minutes, 17 seconds.

Inadvertent or unintentional flight into instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) continues to be a significant cause of fatal helicopter accidents. The crash that killed Kobe Bryant and eight others in January 2020 took place after their helicopter entered clouds during a visual flight rules (VFR) flight. According to the National Transportation Safety Board’s final report on the crash, the pilot succumbed to spatial disorientation and lost control of the helicopter.

Another high-profile accident resulting from inadvertent entry into IMC took place on Feb. 2, 2021. On this occasion, an Idaho National Guard helicopter inadvertently entered clouds in mountainous terrain at night. It flew into the side of a mountain just 14 seconds later, killing all three on board.

Although helicopters can be equipped with instruments to maintain control in these situations — and pilots are trained to use the instruments to fly safely — all agree that the best solution is to avoid IMC. To do this, pilots must have meteorological information.

To start, let’s define IMC. There are two components to it, with either one invoking instrument flight rules (IFR). First is a visibility of less than three miles (five kilometers). Various weather phenomena can impact visibility, including falling precipitation, fog, haze, mist, smoke, or blowing snow, dust or sand. If visibility is within this range, you may not have enough time to safely react to hazards.

Second, it’ll be instrument flight rules if there is a cloud ceiling height of 1,000 feet above ground level or less. The ceiling is defined as the lowest cloud deck covering more than half the sky. The ceiling height is critical due to visibility obstruction. Visibility inside a cloud often goes to near zero, making visual traffic separation impossible. Low ceilings mean that aircraft will have to file an IFR flight plan to ensure adequate separation, or operate under VFR at low altitudes where permitted.

What information is available to identify IMC?

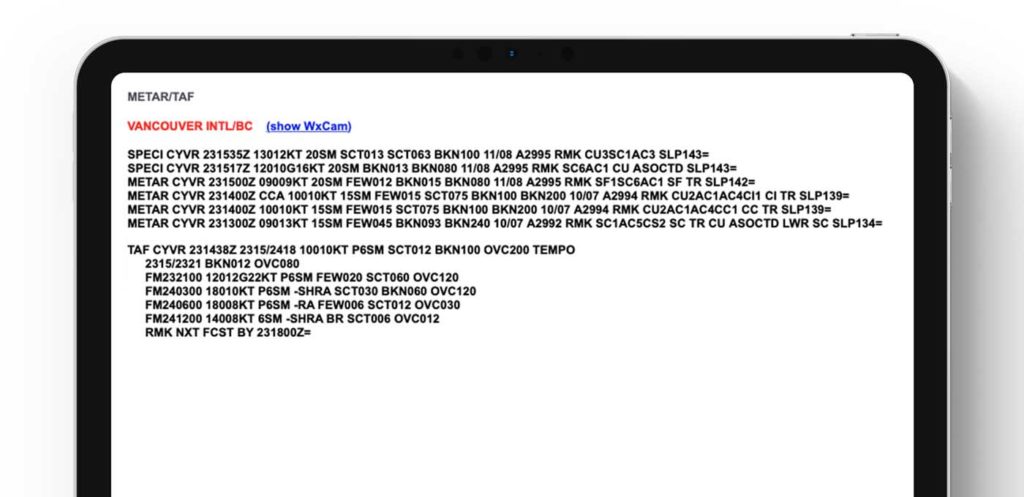

At airports, visibility is critical for the safe takeoff and landing of fixed-wing aircraft. Visibility and ceiling height, if applicable, are therefore measured and reported frequently. Automated weather observing systems (ASOS, AWOS) have the instruments to do this. As for the reporting of these conditions, many airports will generate meteorological aerodrome reports (METARs). These provide current weather information at least on the hour, and typically also when a significant change occurs in one or more critical elements. Now, METARs do not specifically mention IMC, but it can be deduced from the standard report. If broken (BKN) or overcast (OVC) cloud cover is noted, then the given height of that cloud cover will be the ceiling height. Visibility will always be given, and that value can be compared to the IMC criteria.

So, if your takeoff site and/or destination is an airport, the latest METARs will give you the current weather, as well as the recent past (to determine any trends). For aircraft flying at lower elevations (such as helicopters), if there are terminals along your route, you can check the weather conditions at each.

Next, you can check if there are any airmen’s meteorological informations (AIRMETs), which are issued for potentially hazardous weather. They can be given for IMC that covers over 50 percent of a given area at any one time, or if there is extensive mountain obscuration.

Weather radar will show you where precipitation is currently falling. This would usually indicate low cloud bases, but also present the possibility of restrictions in visibility due to the precipitation itself and fog, which typically forms with falling precipitation.

Satellite imagery will show you clouds — but only the tops of the clouds. The actual height of the clouds can be determined by infra-red estimates of the cloud top temperature. Heights can then be estimated by using actual soundings or standard temperature versus height values. Low clouds with possible low ceiling heights can be shown if no cloud decks are above them to block the satellite’s view.

Finally, there are more and more webcams coming online every day. These can be great tools to provide a real-time view of current conditions at a given location.

What forecast information is available?

In the U.S., the National Weather Service’s (NWS’s) 122 local forecast offices produce Terminal Aerodrome Forecasts (TAFs), which give a detailed forecast in three-hour intervals. They cover all terminals within a given forecast area. Aviation Forecast Discussions (AFDs), also produced locally, give a general description of flight conditions out to five days, and any potential IMC will be highlighted. Just go to the NWS homepage (weather.gov) and click on your local office.

On the national scale, the NWS Aviation Weather Center (AWC, aviationweather.gov) gives access to all local products, but also produces regional and national analyses and forecasts. METARs, TAFs, and signification meteorological informations (SIGMETs) are available in text or plotted form, and current radar and satellite images are given. AIRMETs are made here.

Stephanie Avey, techniques development meteorologist at the AWC, specifically recommends the Graphical Forecasts for Aviation (GFA) and the Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) Tool for helicopter operations.

“The GFA is geared toward general aviation, and provides both observation and forecast weather information that pilots can use to plan their flight,” she said. “The HEMS tool is similar, but was specifically designed to meet the needs of short-distance and low-altitude flights common to the HEMS community. We know that for these fliers in particular, rapid changes in ceiling and visibility conditions can be hazardous. The HEMS tool provides an analysis of ceiling and visibility that interpolates between observation points to give a best guess as to the conditions in that area.”

The FAA’s Flight Service Pilot Web Portal (1800wxbrief.com) also has this information, as well as handling pre-flight briefings.

In Canada, NAV Canada’s website has much of the same pertinent weather information: METARs, AIRMETs, and TAFs in alphanumeric format; and flight conditions (including IMC) and GFA in graphical format; as well as radar, satellite, weather maps, and weather cams. Other countries have similar aviation weather services available.

How do meteorologists forecast IMC?

At the national level, meteorologists at the AWC have access to a wealth of information. “We are fortunate to have a wide array of models, satellite, radar, and observations at our fingertips to help provide the best information for our users,” said the AMC’s Avery. “When it comes to forecasting IFR conditions, current observations, satellite imagery, and understanding the overall dynamics of the weather are key.”

On the local level, aviation meteorologists have to deal with smaller-scale effects. Dan Miller, a meteorologist with the NWS Office in Columbia, South Carolina, said, “As far as forecasting flight restrictions in the TAFs, pattern recognition can be important.” In other words, knowing what situations produce low clouds and/or fog in a particular area.

“We use our professional judgment and experience, along with climatology, combined with an array of guidance, including some new high-resolution near term guidance, to make forecast decisions,” Miller explained. “We concentrate detail on the near term where confidence may be highest.”

Jonathan Lamb, a NWS meteorologist in Charleston, South Carolina, said model soundings are particularly useful in forecasting ceilings. “BUFKIT [a local forecast profile visualization tool] is a great tool for looking for saturated layers and predicting cloud ceilings,” he said. “It even has a simulated cloud layer tool that’s surprisingly good. We’re also starting to see more probabilistic model data that includes aviation parameters like probability of IFR ceilings and visibilities.”

“We use our professional judgment and experience, along with climatology, combined with an array of guidance, including some new high-resolution near term guidance, to make forecast decisions.”

Lamb highlighted the Short-Range Ensemble Forecast (SREF) as being one such model that is especially useful. The SREF only goes out to three days, allowing for a smaller forecast time interval. It has one-hour intervals out to 39 hours, and three-hour intervals out to 87 hours. Several numerical models are used (the ensemble within the name) and variations of each model are run concurrently. This technique has been shown to provide more accurate forecasts.

If the IMC is the result of a particular weather system, such as a front or low pressure area, the predicted movement of the system can be used to forecast IMC. If the IMC is the result of a particular weather situation (such as an onshore flow), meteorologists can allow for the development or dissipation of the situation. Local effects such as valley fog and sea fog along the coast are much more difficult to forecast, and often require considerable local experience.

“The forecasting of visibilities and ceiling heights can be extremely challenging and there remains plenty of room for improvement,” said Miller. “Pilots, therefore, are urged to remain aware that unforecast meteorological conditions can occur and to be prepared for [these] accordingly.”

"avoid it" - Google News

May 25, 2021 at 07:44PM

https://ift.tt/3yEkPXq

What tools are available to help helicopter pilots avoid inadvertent IMC? - Vertical Mag - Vertical Magazine

"avoid it" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3844a1y

https://ift.tt/2SzWv5y

No comments:

Post a Comment